The Taste of Liberation: Pary Baban and the Preservation of Kurdish Cuisine

Liberation requires a battle on many fronts, with both arms and tongue, for both land and dignity. Kurdish resistance is defined not only by armed struggle, but also by the preservation of our culture. Forced assimilation and displacement have threatened our existence. In the fight against occupation and ethnic cleansing, we see fighters of many pursuits. Pary Baban is one of those fighters, and this is her story.

A Happy Childhood

Pary Baban was born in Qaladizê, a small town in the Slemani province of Basur, where her family remained until she was six years old. Raised in a big household, including ten siblings and her grandparents, she remembers her childhood as a happy time. Their house was just beside Mount Qalat.

“We used to play around there,” she said. “We used to be very happy in that big family house.”

She remembers climbing up to the top of Mount Qalat and sliding down using cardboard cutouts. Even as a child, she would forage on the mountainside.

Pary Xan’s grandmother was not only the matriarch of the family, she was a prominent member of the community and renowned for her cooking. Before they held large gatherings, many people would send after her to check if their food was well-made.

“She was well-known in Qaladizê,” Pary Xan said.

Her grandmother had her own cows, regularly making yogurt and cheese for charity and selling the livestock for income. As the head of the household, she also managed the family’s finances.

“Granddad was a mallah and a poet,” she said. “He had the old Avesta book.”

Similar to her grandmother, he was also highly regarded in the community. Though he never attended school, he read books in several languages, including Arabic and Farsi. He did not believe in the segregation of genders so he always introduced his daughters to any guests that came over. He refused to place boundaries on the women in his family in order to satisfy gender roles.

Grandmother’s Cooking

On an ordinary day, Pary Xan’s grandmother would place a large cast iron over the fire and collect the ingredients for the dish of the day, usually simple in contents and always rich in flavor. Tomatoes and aubergines, savar (fine bulgur) topped with dates and eggs, baklawa made with homemade dough and clarified butter from her cows, whatever the dish, it was always “cooked to perfection.” Their four cats watched as her grandmother instructed her to grab the herbs. Grandma would make sure to give some milk to the cats too, of course.

“I never forget about that, it’s always in my memory – the way my grandma used to cook.”

Though she did not recognize it at the time, her grandmother would later serve as the foundation of her passion for Kurdish cuisine.

Some dishes required intricate techniques with years of practice to master. In the process of cooking some meats for example, her grandmother would remove the coals and leave only the ash and small embers. She placed the food in the fire pit, covered it with ash to cook evenly, and left it for hours until it was finished.

As the years pass, we notice that practices once seen as outdated or inferior can quickly rise to popularity. Food waste has recently become an important topic in the context of capitalist inefficiency and environmental sustainability. However, the practice of limiting food waste has been maintained in many cultures throughout the world.

Pary Xan’s grandmother would utilize essentially every part of a lamb she was cooking. After it was butchered and cleaned, many of the organs would be saved. One of her specialties was lamb stuffed with a mixture including rice, seasoning, and the liver and heart of the lamb. Everything would be covered in a dough then placed in the tandoor to cook.

In Kurdish communities, food is a symbol of the most important aspects of our culture: tradition, hospitality and respect, kinship and connection.

“When we had guests, she would never cook one or two kilos of rice. She would make the whole bag,” Pary Xan said. The bag would hold approximately 10 kilos of rice.

Whereas feeding guests is considered optional in many western countries, it is obligatory in Kurdish culture and across the region. We know that regardless of the guests, the duration of their stay, the time of day, or their insistence that you do not prepare anything, we must present them with food and drinks. At the very least, they should be offered snacks like fruit, nuts, pastries, and sweets. At mealtimes though, the host must insist that a guest stays to eat with the family.

At weddings in Qaladizê, the rice was different and special for the occasion. They made Mizawra, which included swiss chard, aubergine, and tomato paste. “If you are rich or poor, everyone ate it,” Baban said. She is now working on recreating the dish.

The Uprising

The river near their home was filled with life. Children would swim while the adults made fires or washed clothes.

“In April 1974, during bombardment, my mom and aunt took us to the river,” Pary Xan said.

A hill neighboring the river would be used by the people of Qaladzê as a bunker. “People would hide there,” she said.

When they returned home, everything was destroyed. “I keep remembering that trauma.”

Persecution was not new to the people of Qaladizê. “My grandma said that when she was young, twice before, [the town] was burned down by occupiers.” From one generation to the next, the only inheritance we are guaranteed as Kurdish people are trauma and the will to resist.

“When the occupiers thought there would be a revolt [in Kurdistan], Qaladizê was always a target.”

Pary Xan stated that by 1979, they had destroyed all the villages around Qaladizê – more than 250 villages. As she described the conflict, Baban remembered the martyrs of the uprising. One of them was Deîka Emîna. She was the symbol of the uprising in Qaladizê.

The Flight

In 1988, after taking her exams and just before attending university, Pary Xan’s family was forced to flee to Rojhelat.

“I always thought I would go back and study,” she said. “I was thinking about law school or becoming a teacher, but I never had that chance.”

Saddam was attempting to move people from Qaladizê to the camp. Baban’s family and many others fled to Rojhelat as a result.

“On May 15, 1988, we started walking through the Qandil mountains,” she said. “We went through hell going there.”

Over 500 families fled to Rojhelat together on a journey that lasted nine days. They walked through the night, and when the sun rose they would hide, waiting for darkness to shield them as they continued their flight.

“It feels like the end of your life; you have no hope,” she said. “Only god knows what you are going through.”

The bombardment was continuous. As they fled, they were surrounded by the sounds of incoming mortars and airplanes dropping bombs. Two people were killed during the passage.

“You don’t know what your future will be, if you will be safe or still killed by a bomb.”

Their group was also infiltrated by a man collaborating with the Ba’ath Party. He questioned their reasons for fleeing to Iran and provided the group’s location to the Iraqi military, which then targeted them.

“The mountain was steep and he was on a horse. The moment he disappeared, the bombs started,” she said. He was eventually killed by Peshmerga forces.

Baban highlighted the ways in which armed conflicts have “especially impacted women.” From Rojava to Rojhelat, Kurdish women have been targeted to inflict both physical and psychological harm on our communities. Rape has been used as a weapon of war for millennia and sexual violence is still prevalent in the conflicts of the region – most notably seen in the terrorization of Êzidi women and children by Daesh.

The only foods in their possession as they made the journey were dry bread and dried fruit. In springtime, however, vegetables grew on the mountains they walked through, so they foraged and Pary Xan’s mother used the few ingredients they had to make meals.

Along the way, Pary’s admiration of the dishes and cooking practices in different villages served as a welcomed distraction.

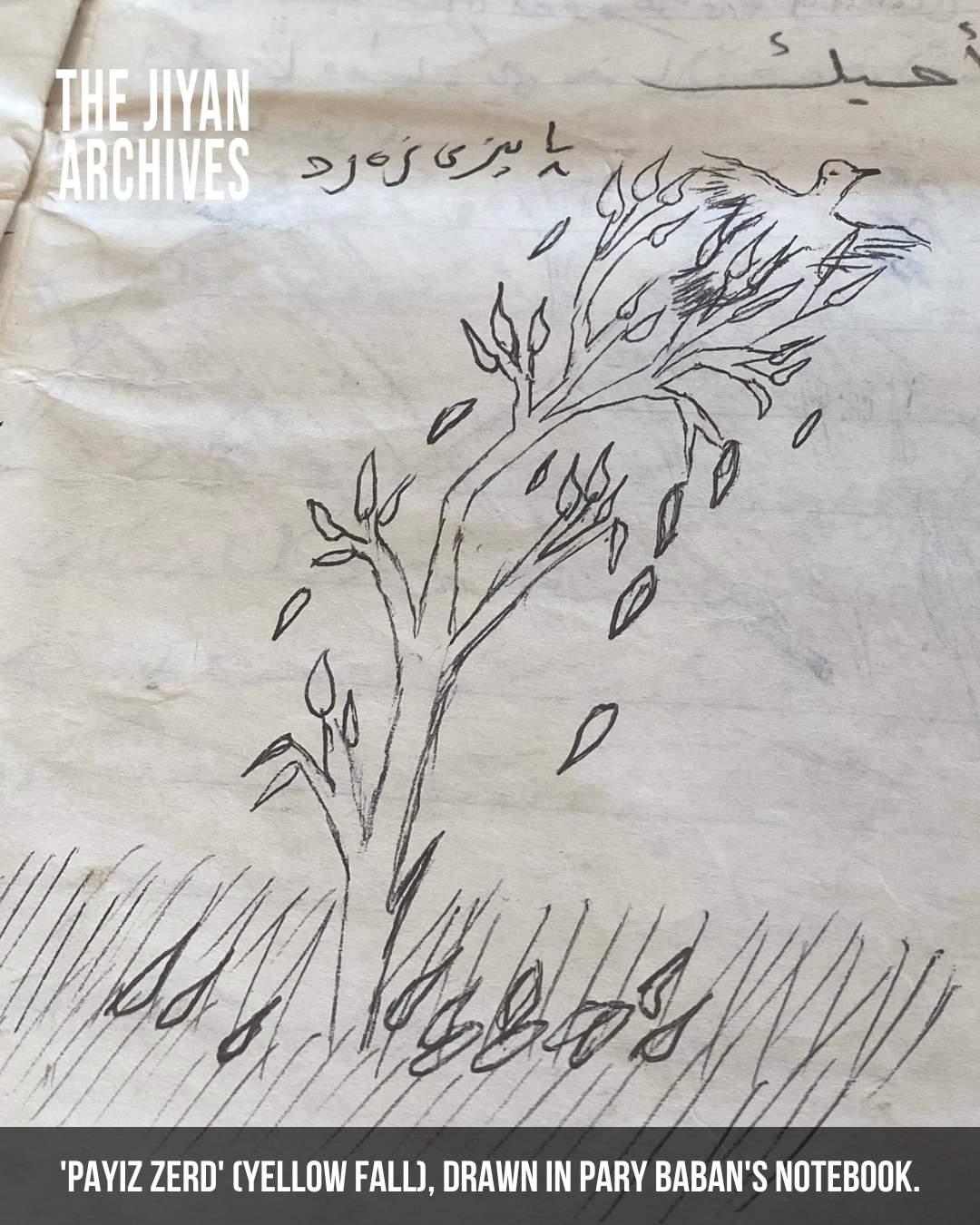

“I wrote all these recipes I learned on the way and at people’s houses,” she said. In a notebook she had, she documented her observations: the vegetables they foraged on the mountain in spring, the herbs they used in different dishes, the methods they used for cooking. She has the notebook to this day.

Recipe entries from 1989:

She noticed a variety of clay pots as they fled Basur. The diza was used to cook food and the goza was a container placed in water to keep its contents cool. One woman who cooked for them used fresh jatra (also known as za’atar or oregano) from the mountain to make kofta.

“It was a dream,” she said. “I can still remember the taste and smell.”

Pary Xan stated that these are the experiences which influence her cooking today. Her dishes embody strong traditions, yet they are the product of constant change.

During her journey, she recalled passing through the village of Kalaxan. “It was heaven on earth, that place.” She wrote poems on the trees. One inscription read, “I hope one day I will come back through here, and it will be free.”

After the long and dangerous journey, Pary Xan and her family arrived in Gwêzê, an area that was controlled by Peshmerga. Many people had relocated there. At that point, her cousin came to get them and they settled down there.

Her family remained in Gwêzê there until 1991, when she came back to Başur for one month. That year, Pary Xan also married her husband, who was a Peshmerga. She moved between Rojhelat and Basur until March of 1992, at which point she moved to Hewlêr, where her family lived in a camp for displaced people.

The situation in the region ultimately led them to leave Kurdistan and move to Europe. They left in October of 1992 and endured yet another difficult migration before they settled down in London.

Rebuilding a Life

In March of 1995, Pary Xan and her family arrived in London. The journey was long and exhausting – she was six months pregnant with her second child at the time.

The difficulties continued after settling down. Building a new life in a foreign country with a foreign language and no community, this is one of the heaviest weights for a person to carry.

She began to study English after they moved to London. She enjoyed learning the language and took many steps to improve her speaking skills.

“When my son was born, I would take him to the park and talk with other moms.”

Soon after, she put her son in nursery school to continue studying English.

“We didn’t have much money,” she said about their first few years in London. In 1998, she and her husband got a kiosk selling convenience store goods. The old owner offered to help them as they learned how to run the store. Baban watched her and quickly learned how to run the store by herself.

“The first customer asked in English slang. He said, ‘Can I have a fag?’ I said, ‘What’s a fag?’ He said, ‘A single cigarette.’”

At 6 am they opened the store for newspapers. At 8 o’clock, Pary would take the kids to school. By 9 am, she was back at the kiosk. She would run the kiosk while her husband bought goods for the store until 3 in the afternoon. At night, he would run the kiosk.

“He likes it when I work with him,” she said. “My husband, he’s very open-minded.”

To this day, many men in our community forbid their wives or daughters from working outside the home, as it continues to serve as a cultural taboo. Baban’s husband never expressed those sentiments, however. “We’ve always been together.”

She said when they got married, she had one şart (condition): “I would go back to uni after we had our kids.” She said he always encouraged her.

“What I achieved, it’s not only me. It’s my husband and my kids as well.”

School, Work, and Parenting

Pary Xan is widely known as a successful chef, but she is also a qualified beauty therapist and hairdresser. In addition to working at the kiosk and parenting, she registered for classes 2002. She attended school for two years and obtained a certificate for hairdressing. Although she did not have time to go to uni, she still wanted to get an education.

Initially, she was dissuaded from registering for the course. She was told it was not a good fit for her because a strong understanding of the English language was required. In response, she said, “No. You try me, I will learn.”

Everyone else in the program was English. She was placed in the lower level group and a few months later moved to the next level. In April, she was the first to complete the course – the rest of the students continued until June. The program chose her for the Student of the Year Award.

She also took computer classes and she registered to study beauty therapy as well, for which she obtained a diploma.

During this time, she was making improvements to the kiosk as well. When people began asking why they did not sell sandwiches, they decided to start ordering sandwiches from a store and selling them at the kiosk. Then, Pary Xan noticed a space behind the kiosk and told her husband that they should submit a request to the council to sell food.

She began to make sandwiches and tea at home and sold them at the kiosk until 2008. That was when they built a new kiosk, Baban Café. At that point, she introduced new items: kobba sawar, vegetarian sandwiches, Yaprax, kebab wraps. “People loved it,” she said.

Over time, she made note of the demand and adjusted accordingly. The majority of the food was “Kurdish with a twist,” she said. She cooked every night until 9 pm and prepared the food for the following day.

Nandine

In 2016, Nandine was born. “From there, it was good and it was bad,” she said.

The name was inspired by a Kurdish elder Pary Xan met at a Newroz party she attended in 2003. The woman told her that nandine is the original Kurdish word for kitchen.

The restaurant faced obstacles and backlash before it even opened. Many people advised her against the concept. They told her it would not bring in revenue because Kurdish food is not well-known. In addition, the restaurant across the street petitioned the council to prevent Nandine from opening because Pary Xan defined it as Kurdish. The majority of signatories were from the Turkish community. Despite everything, she and her family not only opened the Kurdish restaurant, in just a few years they gained immense popularity and recognition.

“This is ours. This is our food, our taste,” Baban said. “I want people to see that we have got a cuisine as well.”

Noting an unfortunate trend of Kurdish chefs using Turkish or Arabic names for traditional Kurdish dishes, she explained that it is essential for us to claim our food and our culture. Many Kurdish restaurant owners continue to label their restaurants as Turkish for a variety of reasons, ranging from their fear of failure as a business to the impact of assimilation.

“This is no good for us,” she said. “It hurts to see all these people not claiming their food. People are afraid to call it Kurdish.”

Some Arab or Persian customers will insist on claiming the food at Nandine or tell them they are making a certain dish wrong. She has refused to let the pressure influence her mission though.

“This is how my grandma cooked it. It’s our heritage,” she said. “We are Kurdish. We are cooking Kurdish cuisine.”

Chef Pary Baban at work in her Nandine kitchen. Photograph: Nandine

On the other hand, Baban has noticed some white chefs dine at the restaurant to co-opt their dishes and label it as “Kurdish-inspired” food. As a small business run by a family that endured immeasurable hardship to reach this point, these actions cannot be described as anything but shameful. Pary’s dishes are a blend of tradition and creativity. They are unique. They require knowledge that cannot be acquired without her. Any efforts to recreate them without permission or credit are as tasteless as the co-opted dishes they produce.

Over the years, however, other Kurdish chefs have visited Nandine to praise Pary and express their gratitude for the work she has done to uplift the community.

“That was very encouraging for me,” she said.

At first Nandine was mostly used as a kitchen for the kiosk in Elephant and Castle, because it was not on a main road. She introduced nani Kurdî (Kurdish bread) with toppings like homemade tomato sauce and za’atar.

With help from her sons Raman and Ranj, she applied for a food stand at Peckham Levels – a converted parking garage that was made up of small businesses. They were chosen out of thousands of applicants and had many customers there until the pandemic began and the establishment was shut down.

During this time, Nandine was beginning to receive more attention for the quality of their food, the unique dishes they served, and the incredible people and story that lie behind it all. Food critic Jay Rayner wrote a commending review of Nandine in 2019 for The Guardian and the year before it was featured in a Vice article. For two years in a row now, Nandine has made the list of 50 Best Restaurants in London by Time Out magazine.

Pary Baban in the dining room at Nandine. Photograph: Sophia Evans/ The Observer

As Nandine’s popularity grew, the restaurant received many reviews. It soon became evident that the dishes resonated with people from around the world.

Pary Xan described one review written by a woman from Pakistan. In it, she “described how unique the food was.”

For a people who are constantly required to justify our existence, Nandine does much more than simply serve people food. The dishes tell our stories, they carry our history.

“Through our food, people can feel our situation and what we have been through,” Pary Xan said.

Currently, she is focusing on a cookbook. “Our food is very rich, but what a shame that it’s not written because of our situation. And that’s my aim. I’m trying to do this: to reclaim these foods,” she said.

Community Education

Adding to the list of her talents and roles, Pary Xan is also an educator and activist in her community. Through her talks on foraging, she provides education on the social and political nature of food while actively preserving a crucial component of Kurdish culture.

“I am putting my culture on the map.”

Her talks cover many aspects of foraging, including the best foods to eat based on the season. Pary has counted at least 57 vegetables and herbs that are foraged and used in Kurdish cuisine. “Now people only eat rice and meat,” she said.

Community building via collaboration with nandine: Pary Baban teaching how to cook kurdish food on a budget with Copleston Peckham community centre.

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

As time goes on, what used to be common practice in the region has quickly become fading knowledge. Access to this knowledge is usually limited to the generation of our grandparents and great grandparents, or to the villages that have maintained an adequate population and have remained undisturbed by fast-food chains and supermarkets.

The significance of Pary Xan’s work became evident as she began to share the names and contents of these traditional dishes, few of which I had heard before we spoke. The dishes often were made for special occasions. Some were cooked for women after childbirth to help aid their recovery, others were made for funerals or weddings. As a result of forced assimilation, much of Kurdish cuisine has either been disappeared from our collective knowledge or consumed by the cultures of our occupiers.

“I want to preserve that culture for my kids, my grandkids,” she said.

I struggled to absorb the abundance of information she provided as she described the foods of each season. The sweetness of springtime was in part due to the sugar from grape molasses. Rice and bamya – okra stew with tomato – was a staple of the summer. The winter consisted of many preserved foods, both dried and pickled. Multiple methods were used for preservation. Food was commonly buried in the ground or placed in caves. Trips to the mountains were frequent for foraging herbs like wild garlic.

“We are very connected to our land. It’s not because it’s Kurdistan, it’s because it’s our land,” she said. “We feed from that land; we live off the land; we look after our land.”

In describing seemingly different aspects of Kurdish culture, Pary Xan made clear that it operates like an ecosystem. “Everything is connected,” she said. Our food, our clothes, our mountains and lakes, our music and dances, the stories of our elders, the languages of the land, they all rely on each other for sustenance.

“You can’t have Newroz without yaprax. You can’t just have the fire, you have to have a picnic.”

Pary Xan said that one way to help preserve the culture is by introducing these practices and traditions to her local community. This is why she chose to become an educator.

“Many people don’t have this opportunity,” she said. “I hope I have done my bit to contribute to my culture.”

Nandine currently have two branches in London, visit to book a table here: https://nandine.co.uk/